By Dave Cauldwell

Article below reproduced from Issue 133 of Wild Magazine, January/February 2013

The spur-winged plover rises into the air on a coastal thermal, hovering briefly before dive-bombing and missing my head by what feels like inches. I cower and stumble towards the cliff edge. Seconds later, it swoops once more. Its mate is on the ground just in front of me, chest puffed out and the yellow spurs on its unfurled wings pointing at me in accusation. She squawks like a high-pitched machine gun. It’s not until I spy four speckled eggs lying on the grass that I deduce why these birds are so cranky.

The spur-winged plover rises into the air on a coastal thermal, hovering briefly before dive-bombing and missing my head by what feels like inches. I cower and stumble towards the cliff edge. Seconds later, it swoops once more. Its mate is on the ground just in front of me, chest puffed out and the yellow spurs on its unfurled wings pointing at me in accusation. She squawks like a high-pitched machine gun. It’s not until I spy four speckled eggs lying on the grass that I deduce why these birds are so cranky.

While witnessing these pint-sized plovers defending their unhatched offspring is fascinating – if not a little disturbing – I’ve come to Yuraygir National Park to steal a glimpse of another bird. Numbering only 100, the coastal emu is teetering on the precipice of extinction. NSW National Parks have adopted it as the symbol of the 65-kilometre Yuraygir Coastal Walk, but despite their ubiquity on the signage, spotting an emu in person may be as tricky as stealing plover eggs.

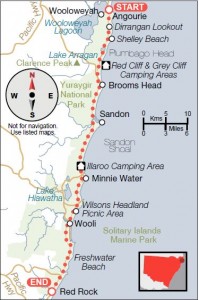

The emu population has been in decline for the past 20 years due to fires during breeding season, predation by foxes, dingoes, feral pigs and dogs, and collisions with vehicles. Their habitat extends from Angourie to Red Rock (the start and finish points of the four-day Yuraygir Coastal Walk), extending in a triangle to Tyndale near the Pacific Highway. Genetic testing has concluded that the coastal emus, separated from their inland counterparts by the Great Dividing Range, aren’t a different species, although it’s possible they could be a sub-species. There are physical differences between the two birds. The coastal emu is smaller and darker, which indicates it has been isolated for a long time.

The sky is unblemished and surfers ride two-metre swells as I set off from Angourie Point. The Yuraygir walk has been open for a couple of years now and encompasses two overlapping eco-systems: Temperate and subtropical. Most of the walk follows clean, curvaceous beaches; laconic villages punctuate the hike and are ideal places to replenish food and water supplies. There are seven national park campsites en route, all within spitting distance of the beach. There are also three river crossings that require boats to ferry you across. These have to be pre-arranged.

Yuraygir National Park was gazetted in 1980 and its gazettal ran in close conjunction with the cessation of sand mining. It may be three decades since minerals were pilfered from the sand, but the legacy of the mining is still very evident today – not that you’d know by looking at the dunes, which are awash with green bitou plants. The bitou’s yellow flowers may add colour to the scene, but these rapacious plants are neither native nor friendly. All native vegetation was removed during the mining, which caused the dunes to collapse. In a bid to restabilise dune structure, mining companies planted the South African bitou plant. It was a cheap, quick and environmentally irresponsible solution. Even though mining ceased in 1977, bitou is far from finished. The 50 000-odd seeds each plant produces annually are spread by birds and other animals and can stay viable in the soil for up to a decade.

I wind my way past clumps of bitou, along the coast to Shelley Beach and past patterned sandstone cliffs with pandanus plants clinging to their sheer edges. A tannin estuary snakes along a deserted beach, a distant cluster of clouds reflected in its sheen. I deviate inland and walk through coastal heathland. Pandanus plants stand like spirally sentinels either side of the track. Coral ferns sway in a sea breeze. I ascend gently until I’m standing atop Dirrangan Lookout where the landscape stretches kilometres before me. The flatness of the arced coastline is contrasted by Clarence Peak, which stands like a conical blip on the horizon. A local woman tells me there have been numerous UFO sightings over this peak.

I wind my way past clumps of bitou, along the coast to Shelley Beach and past patterned sandstone cliffs with pandanus plants clinging to their sheer edges. A tannin estuary snakes along a deserted beach, a distant cluster of clouds reflected in its sheen. I deviate inland and walk through coastal heathland. Pandanus plants stand like spirally sentinels either side of the track. Coral ferns sway in a sea breeze. I ascend gently until I’m standing atop Dirrangan Lookout where the landscape stretches kilometres before me. The flatness of the arced coastline is contrasted by Clarence Peak, which stands like a conical blip on the horizon. A local woman tells me there have been numerous UFO sightings over this peak.

There’s nothing in the sky now except for an azure canvas. I descend to Shelley Beach, tracking over pocked rocks that house thousands of pools, the waters of which reflect the sun countless times. Sea snails have carved artistic and abstract patterns on the bottom of some pools, their sandy trails mixing with the red and grey of rocks and the white and yellow of sand. Below Shelley Headland there is a series of sea caves accessible only at low tide. The caves formed 10 000 years ago when falling sea levels exposed the headland. I enter one through a cavernous walkway and am immersed in a subterranean realm, the landscape of which seems like it’s from a distant planet. Water drips and echoes. Rock ripples on the floor and ceiling in a mixture of pastel blues, browns and reds. I turn back and see the silhouette of a fellow walker and the jagged shape of the blackened cave mouth, both stark against the blue sky.

I exit the cave and hop onto a rocky platform. There used to be an iron stake hammered into the rock here – not to chain up errant emus; diehard fishermen roped themselves to it in rough weather so they could carry on fishing and not get swept away by incoming waves. Further along, the remains of a petrified forest jut up from the sand, defiant stumps that have so far resisted the incessancy of the ocean.

On the shores of Lake Arragan (the first night’s campsite) I get excited when I spot emu prints in the sand. There’s roughly 1.5 metres between each one, which suggests that this particular emu was in a hurry. Coastal emus aren’t as active as their inland relatives, which can travel up to 300 kilometres seasonally. The emus dotted along the Yuraygir coast don’t need to lead such a nomadic lifestyle due to the smorgasbord of food available. They eat bugs, foliage, roots, flowers, ground herbs – even dirt, clay and sand. Pebbles and gravel helps their stomachs break down food.

Fading sunlight tinges peeling paperbark trees orange. I watch the sun dip below Lake Arragan. Its waters are filled with small fish and crustaceans and there is a plethora of birdlife here. The lake’s brackish waters are intermittently flooded by the sea when high tides and stormy conditions erode sand from the beach. As the sand builds up, the lake becomes separated from the ocean once more. The 70-hectare lake extends nearly three kilometres upstream when it isn’t inundated.

Just up from Lake Arragan is Red Cliff, perhaps the most scenic part of the walk where cliffs of grey, blue and red tower up from the beach. It’s here that I encounter the cranky plovers. If I’d stumbled upon a coastal emu’s nest, then there wouldn’t be two birds defending it. Female emus are capricious and can have a couple of males on the go at once. If this is the case, the female will mate with both and then arbitrarily lay her eggs all over the place. She leaves the male to incubate the eggs and he rolls them to a nesting site and sits there for around 55 days. During that time, the male doesn’t eat or drink; he barely poos. The only moisture he gets is off surrounding plants. His metabolism slows right down and he loses around a third of his body weight, standing up just a few times a day to roll the eggs. Once they hatch, the male can stay with his chicks for up to 18 months, missing an entire breeding season to do so.

Somebody who knows about rearing chicks is volunteer wildlife carer Kerry Cranney, who nurses injured and orphaned coastal emus. She also incubates abandoned eggs. Her bush property is five kilometres directly west of where I’m standing now at Red Cliff. The land is ideal for taking care of emus because it’s in the forest and there are no nearby neighbours. Kerry is currently the guardian of 11 emus.

Somebody who knows about rearing chicks is volunteer wildlife carer Kerry Cranney, who nurses injured and orphaned coastal emus. She also incubates abandoned eggs. Her bush property is five kilometres directly west of where I’m standing now at Red Cliff. The land is ideal for taking care of emus because it’s in the forest and there are no nearby neighbours. Kerry is currently the guardian of 11 emus.

‘In previous years, the most I’ve had in care was three at a time,’ she says. ‘This year was the first time that eggs came into my care – we don’t normally find emu nests. The eggs came from a farmer who found a vacant nest while out harvesting his crop. There were 14 eggs when he rang. I knew a number of them were rotten because they were leaking smelly, gooey stuff. I discarded some and put the rest into an incubator.’

The eggs hatched over a two-week period. All of the chicks survived.

‘If those eggs would’ve been with the father then I’m sure five of them wouldn’t have survived,’ Kerry says. ‘The first five chicks were very mobile and the father’s attention would’ve been with them, other than sitting on the nest and incubating the last five. Three or four of those last five had

infections that required antibiotics. One was very unwell for the first couple of months.’

Caring for ten per cent of the entire coastal emu population requires a lot of dedication and maintenance. Each day Kerry is out in the emu enclosure collecting scat.

Her 11 emus do more than 100 poos a day, which she removes to prevent a build up of parasites. There was a period earlier this year when there was eight months of solid rain. With 11 pairs of big emu feet continually pounding the pen, Kerry had to re-dig drains and shift a lot of mud back up hill.

Then there’s the food preparation.

‘Each night I cook up eight to ten kilos of vegetables along with dried grain mixed with pellets. I cook them because emus have a fast digestive system. In the wild they’re eating green grains that are softer and more digestible. Grains you buy from poultry suppliers are dried and that goes straight through their system; they don’t get any nutrients out of it.’

Kerry spends about $100 a week on food at her own expense. WIRES, a wildlife rescue group licensed by National Parks in NSW, reimburses some of that cost.

I stop for a snack at Brooms Head, the first village en route and the site of an old Aboriginal camping area. Along the shoreline there are natural rock walls that form a large enclosure. They are submerged at high tide and this was when Aboriginal fishermen filled the enclosure with pipis (bait) to lure fish. When the water went out, the fish were trapped. Indigofera australis leaves were mushed up and dropped into the water. When broken into pieces, the leaves release toxins that stun the fish. Fishermen cooked their haul on coals, or else rolled them in clay and baked them. The catch was rarely cleaned because once cooked the scales came off easily and the guts rolled into a ball and were easy to extract.

The tide is high this morning so I can’t really see the traps. I climb to the summit of a small hill, passing a rocky outcrop – an old mining site where local tribes fashioned axe heads for hunting. They also traded them with tribes from Maclean and Grafton for koala and kangaroo skins, as well as food. The Yaegl people quarried greywacke and quartzite from Plover Island, a small landmass at the end of the seven-kilometre beach along which I’m walking. They used fishhooks and woomeras instead of more common barbed-bone and shell-tipped spears. Axe heads were ground into shape on rocks and sinew from kangaroo tongues was coiled to attach the axe heads to handles.

Plover Island is but a small dot on the horizon at the moment, as is the coastal arm that houses Sandon – a small village with million-dollar houses and ocean views. Out to sea, I spot the sporadic spurts of humpback whales. I watch as their tails hang in the air, a sign that they’re arching their

backs and rolling forward to dive.

Humpbacks migrate north between May and July from the cold waters of Antarctica to the subtropical breeding grounds off the Queensland coast. These ones are making the long journey back south.

I’ve taken off my shoes and my sweaty feet appreciate the lap of incoming waves; occasionally I’m surprised as the odd wave gets frisky and splashes my crotch. For me, long stretches of beach walking are like moving meditations. With a seemingly endless curve of sand and the expanse of the ocean, this landscape is a gateway to the mind. The repetitive scenery reveals what’s going on inside my head and how my attitude is shaping my experience. I could choose to focus on how hungry I am and how far away my designated lunch spot at Sandon is, but choosing to focus on this overshadows the subtle beauties of the coastline – the idiosyncrasies of shells and pebbles; patterns in the waves; and the noises of gliding seabirds that sing to the rhythm of the waves.

I’ve taken off my shoes and my sweaty feet appreciate the lap of incoming waves; occasionally I’m surprised as the odd wave gets frisky and splashes my crotch. For me, long stretches of beach walking are like moving meditations. With a seemingly endless curve of sand and the expanse of the ocean, this landscape is a gateway to the mind. The repetitive scenery reveals what’s going on inside my head and how my attitude is shaping my experience. I could choose to focus on how hungry I am and how far away my designated lunch spot at Sandon is, but choosing to focus on this overshadows the subtle beauties of the coastline – the idiosyncrasies of shells and pebbles; patterns in the waves; and the noises of gliding seabirds that sing to the rhythm of the waves.

Sandon is the site of my first river crossing. I eat lunch while waiting for a man to arrive and ferry me across the river in his canoe.

It’s approaching dusk as I arrive at Illaroo Camping Area. It’s been a 23-kilometre day and I’m ready to stop walking. I unwittingly pitch my tent next to a spur-tailed plover ‘nest’, ie. a footpath, and get dive-bombed again. I leave the plovers to guard their unborn chicks and head down to the beach to emu spot. A couple of days before emu eggs hatch, the chicks have broken into the air space of the egg and their voices create a whistling sound as air travels through the porous egg. This whistling stimulates the other eggs in the nest to hatch. Emu hatchlings weigh between 350 and 420 grams; the emus Kerry is raising are around 30 kilograms now. Being a surrogate mother, she has to be wary of getting attached.

‘Some carers love having their animals inside, cuddling and kissing them,’ she says. ‘I have to work hard to ensure these animals don’t become so imprinted on me that they become a problem. I’ve known of emus that have been brought up like a family pet and on release they’ve turned into nuisances – some have even become threatening.’

Sexual imprinting is the most severe kind of imprint an emu can acquire. In such cases, a couple of years after release when the males are sexually active they return to the carer’s property and, Kerry says, ‘have tried humping people. We had one emu that was imprinted to motors. Every time a particular fella got on his ride-on mower, he’d have a randy emu on his back. I helped National Parks move that one to a remote area, but it travelled back many kilometres and did the same thing. It ended up dying on the road.’

As part of her caring duties, Kerry has to touch the emus to treat injuries as well as tag and weigh them. She’s careful not to let them get overly familiar with her touch and aims to establish trust, not dependency. After 12 months in her care, Kerry releases the emus into the wild.

‘I don’t just open the gate and ignore them,’ she says. ‘They tend to stay on my property for a number of weeks afterwards, during which time I slowly reduce the amount of supplementary food they get each day so they become more dependent on native food.’

After three sun-drenched days I still haven’t seen an emu. The final day’s hike from Wooli to Red Rock is a grey affair and I cross the river by boat to embark on the most remote section of the walk. Checking tidal charts is essential along this section of coast (just south of Wooli) as it tracks along rocky outcrops, some of which are impassable at high tide or when the sea is rough. Today the tide is high, but not dangerously so. I rock hop over slippery, sharp rocks and through a grove of pandanus plants, passing a coiled up carpet snake. These non-venomous snakes like emu chicks, and one of Kerry’s biggest challenges is to keep her chicks safe from predators like this.

‘I have a constant problem with goannas and carpet pythons,’ she says. ‘Roaming domestic dogs are also an issue. Everyone for kilometres thinks I’m the crazy woman in the bush who’s going to shoot their dog if it comes my way. And I have to work hard to maintain that image! I don’t actually shoot dogs, but I do threaten them because the emus are too valuable.’

Wildlife SOS (Save Our Species) helped Kerry design an enclosure that is goannaand carpet python-proof. When the chicks were very young she wasn’t able to leave her property because she was constantly chasing off goannas. Wildlife SOS provided a large percentage of the materials to build the enclosure and National Parks officers helped construct it. National Parks also came up with additional funds and the manpower to extend Kerry’s pen to incorporate part of her dam. The emus swim in it every day.

I’m nearing the end of the walk and am about to go for a compulsory swim. Between me and the last stretch of beach that leads to Red Rock and the termination of the walk is a chest-deep estuary. I strip off, holding my rucksack aloft and trying not to fall over. A fellow walker stumbles on a submerged rock and ends up with a piece of shell embedded in his foot.

I’m nearing the end of the walk and am about to go for a compulsory swim. Between me and the last stretch of beach that leads to Red Rock and the termination of the walk is a chest-deep estuary. I strip off, holding my rucksack aloft and trying not to fall over. A fellow walker stumbles on a submerged rock and ends up with a piece of shell embedded in his foot.

As Red Rock gets ever nearer, I realise that I’m not going to see any coastal emus this time. But with people like Kerry Cranney around, in coming years there’s a good chance that the coastal emus won’t be so endangered and their presence here will be as noticeable as a dive-bombing plover.

The author would like to thank Debra Novak, Kerry Cranney and Jenny Massie for their invaluable assistance with this article.